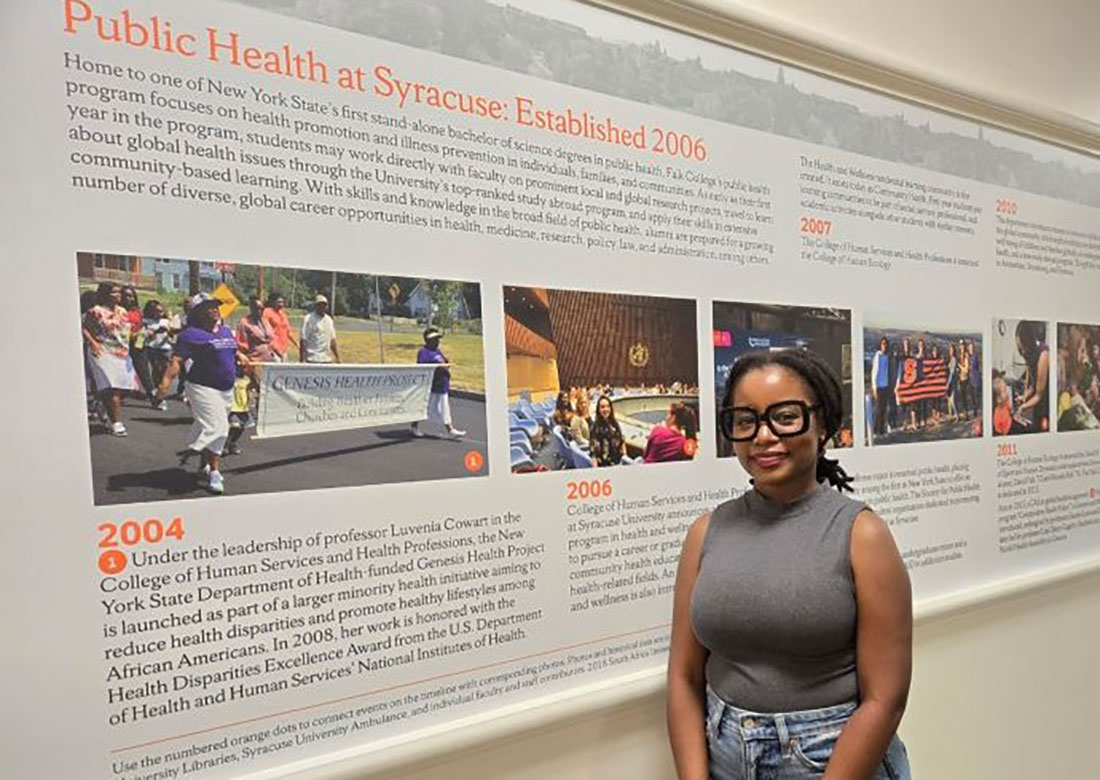

Miriam Mutambudzi will explore how Black adults who reside in historically redlined neighborhoods can experience a disadvantaged occupational life course and subsequent health consequences. Redlining was a discriminatory practice of designating certain neighborhoods, especially predominantly Black ones, as being poor credit risks. Mutambudzi is an assistant professor of public health, a faculty affiliate in the Aging Studies Institute, and a research affiliate in the Center for Aging and Policy Studies and the Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion and Population Health.

In addition to Mutambudzi, an interdisciplinary team of student fellows will work on the project. Students from any discipline and background who are excited about community advocacy and social justice are encouraged to apply for the two-year fellowships. Applications are accepted through early October and fellows are chosen before the end of the fall semester. The faculty-student group will present their findings at a community symposium in 2026. We recently sat down with Mutambudzi to learn more about her project.

Why is this topic important?

This research tackles the ongoing challenges faced by Black communities from the legacy of historical discriminatory housing practices and the subsequent impact of those practices on community members’ employment and health. While the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was enacted as federal law, it failed to fully dismantle racial discrimination in housing resulting from the practice of redlining.

Redlining is a discriminatory practice that began in 1930s America [where] banks and insurance companies refused or limited loans, mortgages and insurance to residents of specific geographic areas—primarily neighborhoods with predominantly Black residents.

Residents of redlined areas had limited access to credit and other financial services and were hindered in their efforts to own homes, invest in property or improve their neighborhoods. The results were often urban decay and a perpetuation of poverty in those areas. While redlining is a historical concept, its effects are very much present today.

Its legacy continues to limit many life opportunities, and neighborhoods with predominantly Black residents where that occurred still face social and economic disadvantages.

How do limited employment prospects—or the lack of a good job—affect health issues?

Both employment and discriminatory policies are key factors contributing to racial disparities in health outcomes. Job insecurity, precarity, lower wages and periods of unemployment—which occur more frequently among Black workers—all contribute to income gaps and limit access to good health insurance and quality healthcare.

Young adults from disadvantaged neighborhoods enter the workforce at a significant disadvantage. Job prospects within their communities are scarce, limiting their ability to find work that pays well, offers stability and provides a path for advancement. This lack of good-quality jobs in their immediate surroundings creates a vicious cycle and the absence of good-quality, stable employment nearby creates a double-edged sword.

Not only are opportunities limited, but these young adults also miss out on crucial skill-building and networking chances that come with t

In addition, involuntary employment interruptions are more frequent for these young adults and further disrupt their career trajectories. This disparity perpetuates a system where economic mobility becomes nearly impossible for those starting from behind.

The cascading constraints imposed by limited job opportunities in disadvantaged neighborhoods have a profound impact on residents’ access to health-promoting resources, creating a cycle that undermines well-being. For example, limited financial resources often translate to poor housing conditions, which may be overcrowded, poorly maintained and may lack essential amenities. Nutritious and organic foods are generally more expensive and less readily available in “food deserts,” leading to a reliance on cheaper, processed unhealthy foods.

The jobs in which Black workers are disproportionately employed may contribute to these health issues, as their work is more likely to be physically and psychologically demanding. All of these factors also combine to contribute to increased risks of health conditions such as obesity, diabetes, respiratory illness and hypertension.